Are you slumped or stacked? How to tell the difference.

Most of us know what slumped is, and what it feels like in our body. I hear the word most often from new students when they first sit in balance – and no one sounds happy about it. I wasn’t either. My front chest, which I was used to lifting, felt disturbingly low.

“Stacked” is a less familiar concept.

If the context is posture, then the association is most likely to be slang for a woman who is, as Online Etymology puts it, “well-built physically; curved in a way considered sexually desirable.” https://www.etymonline.com/word/stacked

In Original Alignment, it’s the spine that’s stacked, not the person. In fact, you can’t be in balance if your spine isn’t stacked. Stacking is so central to Original Alignment, that for a brief, giddy moment during our name search we considered “Stacked” as a name for Noëlle Perez’s work – and then rejected it for obvious reasons.

Stacking begins when you sit with your buttocks behind you, and your weight forward of your sitting bones. Without this base, you can’t stack. The immediate effect, for anyone who lives in modern, pelvis-forward posture, is an increased hollow in the lower back.

The next move is to soften your ribs and let the front of your body drop. When the front ribs drop, they naturally move back, flattening the hollow, and softening the muscles around the spine. With the lumbar spine back in place, your body weight drops as efficiently as possible down to your pelvis and into your chair.

In essence, you give up the exhausting fight against gravity, and settle into your bones.

And despite how it may feel in the front of your body, your spine is longer.

That’s stacked.

Subtract three from your current age, and you’ll have a close estimate of how long it’s been since you felt that sensation. That’s because three is the age when most of us lose our toddler posture and begin to imitate the adults around us. No surprise then, that when your brain reaches for the closest familiar sensation, it comes up with “slumped.”

And this feels unpleasant because slumping isn’t a good thing.

All the way from the word’s Norwegian origins (slumpe: to fall into a bog) through market slumps and athletic slumps, to its current use to describe slack posture, slumping is frowned on.

If you’ve been taught to lift your front ribs, dropping them can feel like an assault on your idea of yourself as someone who is “upright,” with all that implies.

Stacked, on the other hand, is very good indeed.

What does a stacked spine look like?

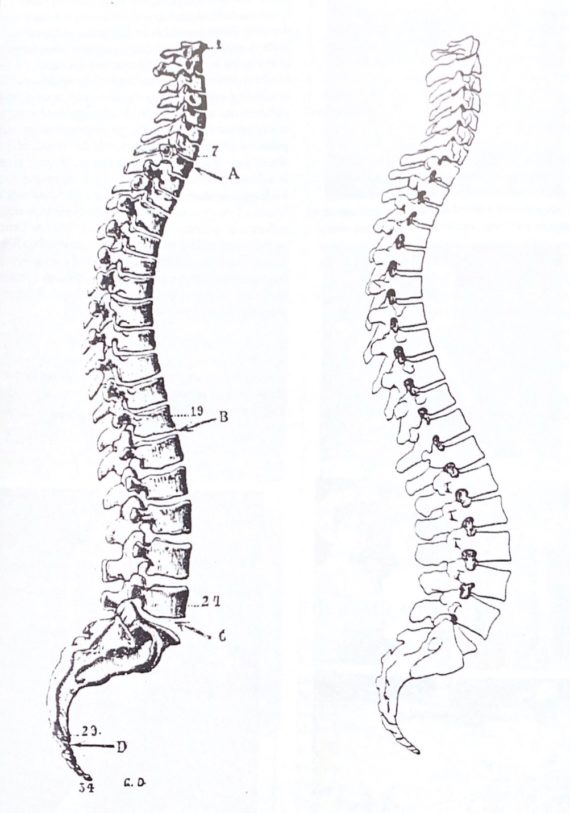

Take a look at the spine on the left, from a 1910 physiology textbook.

The vertebral bodies – the thick flat sections on the front surface of the spine – are as close to horizontal as possible, given the spine’s natural curves. Look particularly at the lower back, the first five bones up from the sacrum at the bottom. Each of the vertebral bodies is close to horizontal. And the empty spaces between bones in the drawing, the spaces filled by our spinal discs, is even front to back.

This spine is stacked. And we can easily imagine how weight transfers through those bones.

What’s the opposite of stacked?

The spine on the right, from a 1990s physiology textbook, has deep curves, especially in the low back. Instead of stacking, the vertebral bodies tilt. The space allowed for the lumbar discs is wide at the front, and narrow at the back.

This is fine when it comes to the first disc, between the sacrum and the lowest vertebra. That disc is wedge-shaped to begin with, to accommodate the curve at the natural arch.

But as we move up the column, we are asking flat discs to take on a wedge shape, which means they are pinched at the back.

Because this spine curves so deeply in the low back, it gives no support to the vertebrae of the upper back. Those bones are in free fall, or would be, without tense, gripped muscles to hold them in place.

In addition, the generous curves in the spine on the right make it significantly shorter than the spine on the left.

Why are these spines so different?

Between 1910 and 1990, “modern posture,” with the pelvis forward, became the norm in industrialized nations. The artists who do anatomical drawings work from cadavers, and they draw what they see. In 1910, the stacked spine was common, by 1990, it was rare.

Here’s what the two spines look like from the outside:

The stacked spine, on the left, creates one long, shallow line from the base of the spine into the neck. This is a healthy spine, with no undue pressure on the discs.

The overly curved spine, on the right, creates a large hollow in the lower back, the upper back rounds outward. Because we are so used to images like these, we read the built-up flesh as muscular and strong. In truth, it’s gripped and tense.

Feeling slumped when you sit in balance doesn’t last. But it’s a necessary first step.

Eventually, sitting in balance feels heavy in the pelvis, and light in the spine. But before length and lightness can arrive, we need to relax and stack. If that feels slumped, so be it.

Our culture has lots of advice to offer about posture – “lift your chest and pull your shoulders back” included. But in our culture, 80 per cent of us will suffer back pain. Could be time to seek a second opinion.

Gravity is mute – or at least it doesn’t use words. But you can listen to gravity, align with it and relax. That’s the one sure route to being stacked.

2 comments on “Are you slumped or stacked? How to tell the difference.”

Thank you for sharing this and your other spinefull insights . So nice to have pictures along your descriptions .

On this USA Thanksgiving day , my heart and body are particularly grateful to your e-mails . Thanks dear Eve . Xo

Charlotte Mandala Sandoz

Ah, Charlotte, it’s good to hear from you, and thank you for the Thanksgiving wishes. The pictures do help, don’t they? I know I need to be able to see something clearly to help me feel it in my body.

Comments are closed.